I love this book. It’s a masterpiece of social comedy and it deserves to be more widely read, so that’s why I’ve decided to rave about it today. Imagine Pride and Prejudice set in the 1930s, and you’ll have some idea of the plot. Not that it’s really about the plot – which, for the record, involves posh English girls attempting to find suitable husbands. The real joy of this novel lies in the characters, particularly Lady Montdore, the wildly ambitious mother of beautiful Polly, who is ‘destined for an exceptional marriage’. Lady Montdore is a monster – self-centred, snobbish, bossy, greedy, completely deluded as to her value in the world – but she’s a very entertaining monster. She provides the author with numerous opportunities to send up the English aristocracy, as in this scene, when Lady Montdore berates our poor narrator, Fanny, the wife of a professor:

I love this book. It’s a masterpiece of social comedy and it deserves to be more widely read, so that’s why I’ve decided to rave about it today. Imagine Pride and Prejudice set in the 1930s, and you’ll have some idea of the plot. Not that it’s really about the plot – which, for the record, involves posh English girls attempting to find suitable husbands. The real joy of this novel lies in the characters, particularly Lady Montdore, the wildly ambitious mother of beautiful Polly, who is ‘destined for an exceptional marriage’. Lady Montdore is a monster – self-centred, snobbish, bossy, greedy, completely deluded as to her value in the world – but she’s a very entertaining monster. She provides the author with numerous opportunities to send up the English aristocracy, as in this scene, when Lady Montdore berates our poor narrator, Fanny, the wife of a professor:

“‘You know, Fanny,’ she went on, ‘it’s all very well for funny little people like you to read books the whole time, you only have yourselves to consider, whereas Montdore and I are public servants in a way, we have something to live up to, tradition and so on, duties to perform, you know, it’s a very different matter . . . It’s a hard life, make no mistake about that, hard and tiring, but occasionally we have our reward – when people get a chance to show how they worship us, for instance, when we came back from India and the dear villagers pulled our motor car up the drive. Really touching! Now all you intellectual people never have moments like that.'”

Of course, things don’t go to plan, and Polly rebels in a manner calculated to drive her mother mad. This sets the scene for the introduction of another wonderful character, Cedric, the heir to the Montdore fortune. It was unusual enough in 1949 (the year the book was first published) for a novel to mention homosexuality, but it was revolutionary to have a happy and openly gay character who charms nearly everyone he meets. He even manages to dazzle the Boreleys, a family notorious for its intolerance:

“‘Well, so then Norma was full of you, just now, when I met her out shopping, because it seems you travelled down from London with her brother Jock yesterday, and now he can literally think of nothing else.’

‘Oh, how exciting. How did he know it was me?’

‘Lots of ways. The goggles, the piping, your name on your luggage. There is nothing anonymous about you, Cedric . . . He says you gave him hypnotic stares through your glasses.’

‘The thing is, he did have rather a pretty tweed on.’

‘And then, apparently, you made him get your suitcase off the rack at Oxford, saying you are not allowed to lift heavy things.’

‘No, and nor am I. It was very heavy, not a sign of a porter as usual, I might have hurt myself. Anyway, it was all right because he terribly sweetly got it down for me.’

‘Yes, and now he’s simply furious that he did. He says you hypnotised him.’

‘Oh, poor him, I do so know the feeling.'”

Then there are Fanny’s eccentric relatives – her wild Uncle Matthew, vague Aunt Sadie, hypochondriacal stepfather Davey, and exuberant little Radlett cousins – with many of these characters inspired by Nancy Mitford’s real family. In addition, the author provides a wickedly funny look at English politics, fashion, marriage and child rearing.

Love in a Cold Climate is actually the second book narrated by Fanny. The first, The Pursuit of Love, was published in 1945. I hesitate to call it a prequel, because that would suggest you need to read it first, and I don’t think you do. It stretches over a longer time period, and is mostly the story of Fanny’s cousin and best friend, Linda (Lady Montdore, Polly and Cedric don’t make an appearance in this one, unfortunately). Some readers prefer this first book to the second, but I think it really depends on whether you regard Linda as a tragic romantic heroine or a spoiled, self-centred brat. As you’ve probably guessed, I’m in the latter camp (I really can’t forgive Linda’s treatment of her hapless daughter). I also think this book ends too abruptly – as though the author suddenly got tired of typing. However, there’s a lot of enjoyment in the descriptions of the Radlett family, so if you adore Love in a Cold Climate, you’ll probably like The Pursuit of Love as well. There’s also a BBC television series based on both books, but I haven’t seen it (and it doesn’t appear to be available in Australia).

Love in a Cold Climate is actually the second book narrated by Fanny. The first, The Pursuit of Love, was published in 1945. I hesitate to call it a prequel, because that would suggest you need to read it first, and I don’t think you do. It stretches over a longer time period, and is mostly the story of Fanny’s cousin and best friend, Linda (Lady Montdore, Polly and Cedric don’t make an appearance in this one, unfortunately). Some readers prefer this first book to the second, but I think it really depends on whether you regard Linda as a tragic romantic heroine or a spoiled, self-centred brat. As you’ve probably guessed, I’m in the latter camp (I really can’t forgive Linda’s treatment of her hapless daughter). I also think this book ends too abruptly – as though the author suddenly got tired of typing. However, there’s a lot of enjoyment in the descriptions of the Radlett family, so if you adore Love in a Cold Climate, you’ll probably like The Pursuit of Love as well. There’s also a BBC television series based on both books, but I haven’t seen it (and it doesn’t appear to be available in Australia).

I’ve previously written about one of Nancy Mitford’s earlier novels, Wigs on the Green (1935), which is interesting for historical and political reasons, but doesn’t have much literary merit. I cannot recommend The Blessing (1951) at all, because it’s awful. However, it and Don’t Tell Alfred (1960) have recently been re-released with lovely illustrated covers.

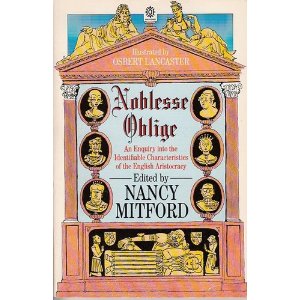

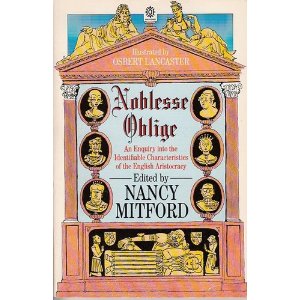

I can recommend Noblesse Oblige: An Enquiry into the Identifiable Characteristics of the English Aristocracy, a biased but very entertaining collection of essays and cartoons about ‘Upper-Class English Usage’, edited by Nancy Mitford and including contributions from Evelyn Waugh and John Betjeman. Laura Thompson has also written a biography of Nancy Mitford called Life in a Cold Climate, which discusses all her books and the influences for her novels.

I can recommend Noblesse Oblige: An Enquiry into the Identifiable Characteristics of the English Aristocracy, a biased but very entertaining collection of essays and cartoons about ‘Upper-Class English Usage’, edited by Nancy Mitford and including contributions from Evelyn Waugh and John Betjeman. Laura Thompson has also written a biography of Nancy Mitford called Life in a Cold Climate, which discusses all her books and the influences for her novels.

See also: Meet The Mitfords

More favourite 1930s/1940s British novels:

1. The Cazalet Chronicles by Elizabeth Jane Howard

2. The Charioteer by Mary Renault

3. The Friendly Young Ladies by Mary Renault