Yes, my holidays ended a fortnight ago and I’m only now getting around to blogging about the books I read.

Lady in Waiting: My Extraordinary Life in the Shadow of the Crown by Anne Glenconner was exactly what the title suggests — a memoir of Princess Margaret’s lady-in-waiting, who was married to Colin Tennant, one of those badly-behaved rich aristocrats who enjoyed hanging out with celebrities. Tennant had numerous affairs, enjoyed bullying his family, delighted in eccentric behaviour such as pulling off his own underwear and eating it, and spent most of his time throwing enormous ‘uncontrollable’ tantrums in public (yet, oddly enough, he was able to restrain himself in the presence of people more powerful than he was, such as the Queen). Lady Anne coped with his abuse by travelling the world with Princess Margaret and finding a boyfriend of her own. Meanwhile their eldest children were left in the care of various sadistic and incompetent nannies, then sent off to boarding school. Unsurprisingly, their eldest son developed mental health problems. He was a heroin addict by the age of 16, was disinherited by his father, then died of hepatitis. Their second son, unexpectedly finding himself the heir to the family title, dutifully got married and produced a son, then came out as gay, left his wife and died of AIDS. Meanwhile, their third son had been nearly killed in an accident caused by his reckless behaviour and spent years in rehabilitation re-learning how to walk and talk. (There were also twin girls, who were ignored because they were female.) I spent the book alternately despising Anne for being a doormat and feeling desperately sorry for her. It’s a fascinating, appalling look at some very privileged, very repressed British people. Mitford fans will adore this.

Lady in Waiting: My Extraordinary Life in the Shadow of the Crown by Anne Glenconner was exactly what the title suggests — a memoir of Princess Margaret’s lady-in-waiting, who was married to Colin Tennant, one of those badly-behaved rich aristocrats who enjoyed hanging out with celebrities. Tennant had numerous affairs, enjoyed bullying his family, delighted in eccentric behaviour such as pulling off his own underwear and eating it, and spent most of his time throwing enormous ‘uncontrollable’ tantrums in public (yet, oddly enough, he was able to restrain himself in the presence of people more powerful than he was, such as the Queen). Lady Anne coped with his abuse by travelling the world with Princess Margaret and finding a boyfriend of her own. Meanwhile their eldest children were left in the care of various sadistic and incompetent nannies, then sent off to boarding school. Unsurprisingly, their eldest son developed mental health problems. He was a heroin addict by the age of 16, was disinherited by his father, then died of hepatitis. Their second son, unexpectedly finding himself the heir to the family title, dutifully got married and produced a son, then came out as gay, left his wife and died of AIDS. Meanwhile, their third son had been nearly killed in an accident caused by his reckless behaviour and spent years in rehabilitation re-learning how to walk and talk. (There were also twin girls, who were ignored because they were female.) I spent the book alternately despising Anne for being a doormat and feeling desperately sorry for her. It’s a fascinating, appalling look at some very privileged, very repressed British people. Mitford fans will adore this.

I’d wanted to read The Weekend by Charlotte Wood ever since I heard her speak about the process of writing it a few years ago. This is an engrossing novel about three older women who gather to clear out their dead friend’s holiday house at Christmas. There are a lot of sharp, funny observations about friendship, men, families and ageing, although there’s not much compassion in the author’s gaze. I expected to find the characters unlikeable, which they were, but they were always interesting enough to keep my attention. I can’t say the women and their experiences are ‘typical’ — one is a celebrity chef, one a famous actress and the other a ‘public intellectual’ whose books are international bestsellers. The characters all live in modern-day Sydney and yet everyone in the novel is white and middle-class (with the exception of a young priest who briefly appears at the end and is “Filipino, Wendy thought”). I also never quite understood why the characters remained friends when they seemed to dislike each other so much. However, my main issue with this book was the final chapter, which veers so wildly into melodrama and cliché that it seemed to have been tacked on from an entirely different novel. Book clubs will love this, because there’s so much to discuss.

I’d wanted to read The Weekend by Charlotte Wood ever since I heard her speak about the process of writing it a few years ago. This is an engrossing novel about three older women who gather to clear out their dead friend’s holiday house at Christmas. There are a lot of sharp, funny observations about friendship, men, families and ageing, although there’s not much compassion in the author’s gaze. I expected to find the characters unlikeable, which they were, but they were always interesting enough to keep my attention. I can’t say the women and their experiences are ‘typical’ — one is a celebrity chef, one a famous actress and the other a ‘public intellectual’ whose books are international bestsellers. The characters all live in modern-day Sydney and yet everyone in the novel is white and middle-class (with the exception of a young priest who briefly appears at the end and is “Filipino, Wendy thought”). I also never quite understood why the characters remained friends when they seemed to dislike each other so much. However, my main issue with this book was the final chapter, which veers so wildly into melodrama and cliché that it seemed to have been tacked on from an entirely different novel. Book clubs will love this, because there’s so much to discuss.

My favourite holiday read was definitely The Wych Elm by Tana French, a crime thriller with a literary bent that reminded me of the novels Ruth Rendell used to write under her ‘Barbara Vine’ pseudonym. The twists of the murder mystery plot kept me turning the pages eagerly, but this was also an intelligent exploration of privilege, identity and memory. Golden boy Toby is handsome, clever and rich, with a loving, stable family and a devoted, beautiful girlfriend. He begins by saying “I always considered myself to be, basically, a lucky person”, but his life changes in an instant when he’s the victim of a violent home invasion. Physically and psychologically damaged, he goes to stay with his dying uncle in the family mansion. And then a body is discovered inside an elm tree in the garden and Toby gradually learns just how privileged his previous life had been… Some fans of this author have complained that this was too slow and a disappointment compared to her earlier crime series set in Dublin. I haven’t read her previous books, but I thought Toby’s rambling, repetitious narration was characteristic of someone recovering from a traumatic brain injury and I tore through the nearly 500 pages in two days. It was a grim read at times, but a satisfying one and I’m keen to read more of this author’s work now. (I was also filled with horrified admiration for someone who could dream up the notion of a dead body in a tree until I discovered that this actually happened and the real-life mystery of Bella in the Wych Elm remains unsolved.)

My favourite holiday read was definitely The Wych Elm by Tana French, a crime thriller with a literary bent that reminded me of the novels Ruth Rendell used to write under her ‘Barbara Vine’ pseudonym. The twists of the murder mystery plot kept me turning the pages eagerly, but this was also an intelligent exploration of privilege, identity and memory. Golden boy Toby is handsome, clever and rich, with a loving, stable family and a devoted, beautiful girlfriend. He begins by saying “I always considered myself to be, basically, a lucky person”, but his life changes in an instant when he’s the victim of a violent home invasion. Physically and psychologically damaged, he goes to stay with his dying uncle in the family mansion. And then a body is discovered inside an elm tree in the garden and Toby gradually learns just how privileged his previous life had been… Some fans of this author have complained that this was too slow and a disappointment compared to her earlier crime series set in Dublin. I haven’t read her previous books, but I thought Toby’s rambling, repetitious narration was characteristic of someone recovering from a traumatic brain injury and I tore through the nearly 500 pages in two days. It was a grim read at times, but a satisfying one and I’m keen to read more of this author’s work now. (I was also filled with horrified admiration for someone who could dream up the notion of a dead body in a tree until I discovered that this actually happened and the real-life mystery of Bella in the Wych Elm remains unsolved.)

Finally, two books that ended up being not what I expected or what I really wanted to read, but that’s not the fault of these authors, who have both written thoughtful, well-researched historical novels.

The Fountains of Silence by Ruta Sepetys sounded as though it would be exactly my cup of tea — a novel set in Fascist Spain in the 1950s. The story involves the ‘stolen children’, the tens of thousands of babies stolen from Republican families and other ‘enemies of Spain’, who were sent to orphanages and then adopted by the Spanish political elite and rich foreigners. Ana, from a poor and traumatised Republican family, is working at a hotel in 1957 when she meets Daniel, aspiring photojournalist and son of a Texan oil tycoon. A forbidden romance blossoms, but Daniel doesn’t understand just how repressive, corrupt and dangerous Franco’s regime is. The author’s research is thorough and wide-ranging, the setting is fascinating and I learned a lot about post-war Spain. However, I found the story too soap-opera-ish for my tastes, involving a lot of amazing coincidences and clunky dialogue. I think I would have preferred to read non-fiction about this subject, but I’m sure a lot of readers will find this novel engrossing.

The Fountains of Silence by Ruta Sepetys sounded as though it would be exactly my cup of tea — a novel set in Fascist Spain in the 1950s. The story involves the ‘stolen children’, the tens of thousands of babies stolen from Republican families and other ‘enemies of Spain’, who were sent to orphanages and then adopted by the Spanish political elite and rich foreigners. Ana, from a poor and traumatised Republican family, is working at a hotel in 1957 when she meets Daniel, aspiring photojournalist and son of a Texan oil tycoon. A forbidden romance blossoms, but Daniel doesn’t understand just how repressive, corrupt and dangerous Franco’s regime is. The author’s research is thorough and wide-ranging, the setting is fascinating and I learned a lot about post-war Spain. However, I found the story too soap-opera-ish for my tastes, involving a lot of amazing coincidences and clunky dialogue. I think I would have preferred to read non-fiction about this subject, but I’m sure a lot of readers will find this novel engrossing.

Exposure by Helen Dunmore was also very well-researched. Set in England in 1960, the book jacket suggests it’s a fast-paced thriller about Cold War spies. It’s actually an extremely slow-moving account of a British civil servant accused of espionage and the effect of this scandal on his German-born wife and their three young children. There is a lot of fascinating detail about the grimness of English life and while none of the characters are particularly warm or likeable, they are carefully portrayed. It was just a bit of a slog to get through, because nothing very exciting happened until the final chapter. In fact, it ends just where I thought it should have started. I would probably have enjoyed this more if I’d begun the book with more realistic expectations. Note to publishers: write accurate blurbs on your book jackets!

Exposure by Helen Dunmore was also very well-researched. Set in England in 1960, the book jacket suggests it’s a fast-paced thriller about Cold War spies. It’s actually an extremely slow-moving account of a British civil servant accused of espionage and the effect of this scandal on his German-born wife and their three young children. There is a lot of fascinating detail about the grimness of English life and while none of the characters are particularly warm or likeable, they are carefully portrayed. It was just a bit of a slog to get through, because nothing very exciting happened until the final chapter. In fact, it ends just where I thought it should have started. I would probably have enjoyed this more if I’d begun the book with more realistic expectations. Note to publishers: write accurate blurbs on your book jackets!

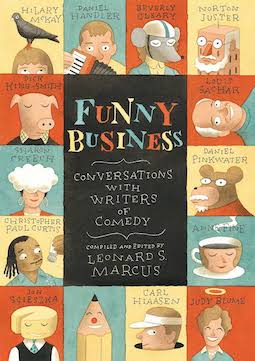

“A joke isn’t a joke if you need to explain it,” says Leonard S. Marcus, who compiled and edited this series of interviews with authors of funny books for children. “Even so, the hidden clockwork of comedy has long been considered one of the great riddles of life.”

“A joke isn’t a joke if you need to explain it,” says Leonard S. Marcus, who compiled and edited this series of interviews with authors of funny books for children. “Even so, the hidden clockwork of comedy has long been considered one of the great riddles of life.”

This year, I failed to finish reading a number of novels that had received a great deal of hype. It is possible there’s something wrong with my literary tastes, but I feel life is just too short to waste a lot of time ploughing through pretentious waffle about uninteresting characters and situations. I did enjoy the latest Rivers of London novel from Ben Aaronovitch,

This year, I failed to finish reading a number of novels that had received a great deal of hype. It is possible there’s something wrong with my literary tastes, but I feel life is just too short to waste a lot of time ploughing through pretentious waffle about uninteresting characters and situations. I did enjoy the latest Rivers of London novel from Ben Aaronovitch,  I really liked

I really liked  I read some great books aimed at middle graders.

I read some great books aimed at middle graders.

Finally, I absolutely loved

Finally, I absolutely loved