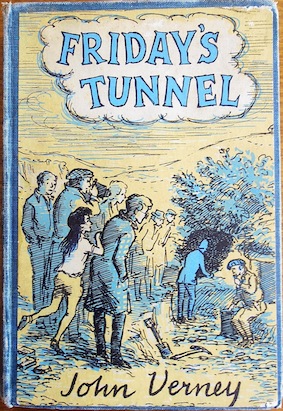

A note for the benefit of those new to this series: ‘dated’ means ‘of its time, not ours’. ‘Dated’ books can be horribly offensive to modern sensibilities, or they can be charmingly nostalgic, or they can simply be a bit . . . odd. Friday’s Tunnel by John Verney falls mostly into the charmingly nostalgic category, with the dated bits generally being amusing, rather than annoying. It was recommended to me by Debbie during my search for 1950s schoolgirl books, so thank you, Debbie – I thoroughly enjoyed this book (and took careful notes on the schoolgirl slang, hobbies, clothes and other useful information contained therein). But first I ought to show you the lovely old hardcover I purchased from Rainy Day Books:

This was once a library book at the ‘City of Collingwood Junior Library’ and the following letter to ‘Junior Borrowers’ is pasted in the front:

I wish all the adults who borrow books from my local library would follow that advice.

I should also point out that my 1959 (first?) edition includes lots of great illustrations by the author, as well as a detailed map (which certainly came in handy, given the complicated plot).

Friday’s Tunnel is narrated by February Callendar, who we learn is “stuck in bed for ages with a broken nose, a broken pelvis and a broken several other things” and is therefore at leisure to write down the extraordinary story of how she managed to save the world during her summer holidays, when she’d actually planned to spend all her time practising show jumping for the district gymkhana and improving her overarm tennis serve (both of which turn out to be very useful skills when dealing with the villains). She also explains that she intends to write “the sort of book I like to read, which means one with a map and drawings, and talk on every page and not one with long descriptions about the sun’s early rays touching the feathery beech-tips with gold and gossamer quivering in the dew, because I think dew is soppy and anyway I’m usually still asleep when all that sort of thing is going on”.

February’s adventure reminded me quite a lot of the Tintin books, even though she herself never actually leaves England. It involves, among other things, a world crisis triggered by a (possibly fake) coup d’état in a small island kingdom called Capria, a mysterious mineral that might be capable of blowing up the world, a millionaire businessman and his vulgar wife, a mysterious plane crash, a missing journalist, a dead body in a canal, a celebrity racing car driver, secret tunnels, a sinister sweet shop owner and a newspaper cartoon strip that may (or may not) contain vital coded messages.

And as with Tintin, the attitudes are from the 1950s. The villains are all swarthy and “foreign-looking”, even if they’re British. The Caprian President, Umbarak, however, was educated at Harrow, so he is “a Christian and a highly civilised man with Western ideas who had enabled the Caprians to live free of fear for the only time in history”, whereas his half-brother Zayid, the coup leader, is “just a bandit like his Moslem forefathers . . . mixed up in every racket in the Mediterranean and the Middle East”. Umbarak has “a gentle, beautiful face like a prince in a fairy tale” and is described as a “saint”, while Zayid looks “splendidly fierce”. I don’t think Zayid is actually Muslim, though, because he drinks alcohol, gambles, sells dope and smuggles “Jewish emigrants into Palestine”. It must also be noted that February and her brother Friday are much more sympathetic towards Zayid (February thinks he sounds “more fun” and she “rather sympathised with him for shutting Umbarak up in the Jenin Palace”, while Friday thinks Umbarak sounds “wet” and that one of Zayid’s more ingenious dope-smuggling rackets is “a wizard idea”). A friend of February’s father, a Very Important Man in the War Office, later gives a pompous speech about how Britain ought to take charge of all the stock of the mineral caprium because “England is the only Great Power who could use caprium as it must be used if the world is to survive”, although his view is countered by the newspaper editor who says, “We happen to believe that if the world is to survive, Great Powers simply must stop grabbing everything they think they can get away with and try behaving openly for a change.” (Sadly, the current leaders of the Great Powers do not appear to agree with this last viewpoint. And I think the characters in this book are being overly optimistic to describe Britain in 1959 as a “Great Power”.)

But it was all the science-y bits that had me either groaning or laughing at their dated-ness. I’ve noticed during my recent 1950s reading that fiction writers of the time seemed obsessed with the notion that science was about to annihilate humanity (which I guess is understandable after nuclear bombs destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945) and that all scientists, but especially physicists, were believed to be secretive, incomprehensible and slightly deranged. So I was not surprised to see that science plays a large role in this book. A schoolboy friend of February’s is “mad on chemistry” and is constantly doing dangerous experiments (which, by the way, cause no concern to his parents, even when he burns off his sister’s hair with acid). He buys a lot of different cigarette brands (one of which is supposed to be “non-cancer”) to test, and wonders why one is wrapped in paper that won’t burn. His father, the village doctor, thinks the paper is probably made of asbestos:

“No reason why it shouldn’t be used instead of tin-foil,” he said. “Perhaps it preserves the cigarettes better in some way.”

Then he wanders off (probably smoking his pipe). Mind you, this is the same doctor who cheerfully discusses his patients’ details with February, explaining that the old woman he’s about to see only has a fever because she “gets herself so excited with all the things she thinks are wrong with her” so he’s going to give her “the nastiest tasting medicine I can think of, which is asafoetida and bromide”. Which is probably an accurate description of the behaviour of doctors, in the days before anyone paid much attention to ideas like “patient confidentiality” and “evidence-based medicine”.

But the funniest part was when the War Office bigwig gave a solemn lecture on physics, explaining that uranium is “the heaviest” element and that Britain’s “top nuclear physicist has had a nervous breakdown” because the mysterious mineral caprium has “upset his confidence in himself” and he’s been forced to accept that “all his knowledge is no less ludicrous than was the flat earth theory in its day”. I’m pretty sure “top nuclear physicists” don’t usually go “round the bend” when they come across a new, interesting element (isn’t that what they hope for?) and in any case, the reported properties of caprium don’t actually seem to prove that the atomic theory is wrong. (Also, despite no one understanding what caprium does, the War Office bigwig straps a bag of (possibly radioactive) caprium to his abdomen to cure his duodenal ulcer, which, of course, has been caused by the stress of dealing with the caprium crisis.)

Overall, though, I enjoyed February’s story very much. Her voice is lively and often very funny, her eccentric family and friends are entertaining, and the dated bits are quite amusing. Recommended for fans of Tintin or for those who wish the Famous Five books had had more plausible characters and more complex plots.

More ‘dated’ books:

1. Wigs on the Green by Nancy Mitford

2. The Charioteer by Mary Renault

3. The Friendly Young Ladies by Mary Renault

4. Police at the Funeral by Margery Allingham

5. Emil and the Detectives by Erich Kästner

6. The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

7. Swallows and Amazons by Arthur Ransome

8. Kangaroo by D. H. Lawrence

_____

Shaun Tan’s The Arrival was a beautiful wordless story about a refugee starting a new life in a strange, confusing country, with a message particularly relevant to the world right now. On a lighter note, I enjoyed Kate Beaton’s The Princess and the Pony, about a young warrior princess who hopes to receive a noble steed for her birthday but instead finds herself stuck with a small, round pony with some unfortunate traits.

Shaun Tan’s The Arrival was a beautiful wordless story about a refugee starting a new life in a strange, confusing country, with a message particularly relevant to the world right now. On a lighter note, I enjoyed Kate Beaton’s The Princess and the Pony, about a young warrior princess who hopes to receive a noble steed for her birthday but instead finds herself stuck with a small, round pony with some unfortunate traits.

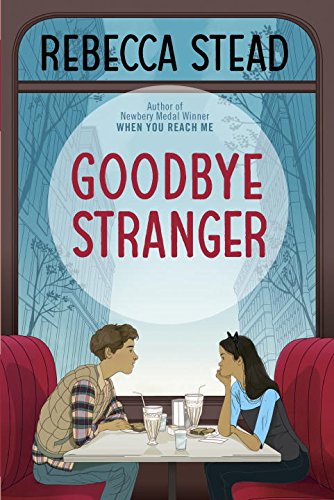

The plot revolves around a sexting scandal. Why did Emily send a revealing photo of herself to Patrick when she promised Bridge that she wouldn’t? Who sent that photo to all the boys in eighth grade? Does this mean Emily is a “skank”? Should Sherm tell the principal what he knows, even though he’ll be ostracised by the other boys if he does? If Patrick wasn’t responsible, then who is he protecting with his silence? Why does Emily insist on staying loyal to Patrick? And who revenge-posted that revealing photo of Patrick? There’s also a rather confusing subplot set several months into the future, involving an unnamed older teenager responsible for another scandal and narrated in the second person. Other relationships are shown in order to further explore the theme of love – for example, Emily’s parents have divorced but they still go on dates, Sherm’s grandfather has walked out on his wife after fifty years of marriage, and Tab’s mother observes Karva Chauth (when “Good Hindu women fast all day to show their devotion to their husbands”, which Tab thinks is anti-feminist, although her older sister Celeste thinks it’s “romantic”).

The plot revolves around a sexting scandal. Why did Emily send a revealing photo of herself to Patrick when she promised Bridge that she wouldn’t? Who sent that photo to all the boys in eighth grade? Does this mean Emily is a “skank”? Should Sherm tell the principal what he knows, even though he’ll be ostracised by the other boys if he does? If Patrick wasn’t responsible, then who is he protecting with his silence? Why does Emily insist on staying loyal to Patrick? And who revenge-posted that revealing photo of Patrick? There’s also a rather confusing subplot set several months into the future, involving an unnamed older teenager responsible for another scandal and narrated in the second person. Other relationships are shown in order to further explore the theme of love – for example, Emily’s parents have divorced but they still go on dates, Sherm’s grandfather has walked out on his wife after fifty years of marriage, and Tab’s mother observes Karva Chauth (when “Good Hindu women fast all day to show their devotion to their husbands”, which Tab thinks is anti-feminist, although her older sister Celeste thinks it’s “romantic”).