The Secret to Superhuman Strength is Alison Bechdel’s latest graphic memoir. It’s a characteristically funny, thought-provoking read, but also makes me very glad I’m not Alison Bechdel’s friend, relative or partner because she splatters everything on the page. It’s probably small consolation to them that she’s even harder on herself than she is on everyone else. This memoir, her third, is about her obsession with exercise—skiing, cycling, strength training, running, yoga, karate and trying out every exercise fad since the 1980s. Her focus on a healthy body does not prevent her from abusing alcohol, recreational drugs and prescription drugs, and having the worst sleep habits ever, just as her desire for secure love does not stop her incessant chasing after unsuitable women, even when she’s already in a relationship. She attempts therapy of various kinds, investigates Buddhism, and seeks wisdom in the lives and works of Kerouac, the Wordsworths, Shelley, Coleridge, Emerson and Margaret Fuller, until she finally realises:

The Secret to Superhuman Strength is Alison Bechdel’s latest graphic memoir. It’s a characteristically funny, thought-provoking read, but also makes me very glad I’m not Alison Bechdel’s friend, relative or partner because she splatters everything on the page. It’s probably small consolation to them that she’s even harder on herself than she is on everyone else. This memoir, her third, is about her obsession with exercise—skiing, cycling, strength training, running, yoga, karate and trying out every exercise fad since the 1980s. Her focus on a healthy body does not prevent her from abusing alcohol, recreational drugs and prescription drugs, and having the worst sleep habits ever, just as her desire for secure love does not stop her incessant chasing after unsuitable women, even when she’s already in a relationship. She attempts therapy of various kinds, investigates Buddhism, and seeks wisdom in the lives and works of Kerouac, the Wordsworths, Shelley, Coleridge, Emerson and Margaret Fuller, until she finally realises:

“that you can’t repress pain and still expect to feel pleasure. And that feeling pain compared with the gray dread of avoiding it, was actually almost a kind of joy. In fact, joy was only possible because one’s existence—all this!—was going to end. What a tedious slog life would be without death!”

I also really liked The War of Nerves: Inside the Cold War Mind by Martin Sixsmith. It uses psychological analyses of Cold War leaders, from Churchill and Stalin to Reagan, Thatcher and Gorbachev, as well as whole-population studies, to examine how the fear, tension and paranoia in both East and West changed world history. The author studied Russian and psychology in the UK, US and USSR, and worked as a journalist in Moscow at the end of the Cold War, so his perspective is well-informed and fascinating. The edition I read was published in 2021, before Putin invaded Ukraine, so it would be interesting to read an updated edition (although I now see that he published a book last year about Putin).

I also really liked The War of Nerves: Inside the Cold War Mind by Martin Sixsmith. It uses psychological analyses of Cold War leaders, from Churchill and Stalin to Reagan, Thatcher and Gorbachev, as well as whole-population studies, to examine how the fear, tension and paranoia in both East and West changed world history. The author studied Russian and psychology in the UK, US and USSR, and worked as a journalist in Moscow at the end of the Cold War, so his perspective is well-informed and fascinating. The edition I read was published in 2021, before Putin invaded Ukraine, so it would be interesting to read an updated edition (although I now see that he published a book last year about Putin).

I know everyone has already read The Thursday Murder Club by Richard Osman, but I avoided it because something that popular written by a television celebrity would have to be bad, right? I was wrong. It’s a clever and very amusing mystery set in a retirement village, in which four elderly residents solve crimes with the reluctant help of a depressed detective inspector and his cheery sidekick. The plot does go completely off the rails towards the end, with three unconnected murders getting solved, several deaths, a Murder Club member reuniting with her estranged daughter, and the depressed detective gaining a girlfriend. There were just too many characters, too many red herrings, and not enough space devoted to the four main characters, who were all fascinating and funny.

I know everyone has already read The Thursday Murder Club by Richard Osman, but I avoided it because something that popular written by a television celebrity would have to be bad, right? I was wrong. It’s a clever and very amusing mystery set in a retirement village, in which four elderly residents solve crimes with the reluctant help of a depressed detective inspector and his cheery sidekick. The plot does go completely off the rails towards the end, with three unconnected murders getting solved, several deaths, a Murder Club member reuniting with her estranged daughter, and the depressed detective gaining a girlfriend. There were just too many characters, too many red herrings, and not enough space devoted to the four main characters, who were all fascinating and funny.

I preferred the next book in the series, The Man Who Died Twice. The plot is still complex, but at least this time, the crimes are all linked and because they are related to the Secret Service past of enigmatic Elizabeth, the elaborate plot twists seem more plausible. There’s more attention paid this time to the relationships between the Murder Club members, which is very satisfying. Ibrahim is attacked and the others take revenge; Ron gets to act out his thuggish fantasies; Joyce’s narration is laugh-out-loud funny and her badly-knitted friendship bracelets become not only a running joke but an important clue. I’m looking forward to reading the other books in the series—although of course, there’s an enormous waiting list for them at the library. Apparently a film of the first book is being released this year.

What a great start to my 2024 reading! I loved

What a great start to my 2024 reading! I loved  I enjoyed

I enjoyed  I had

I had  I then read a lovely book about trees.

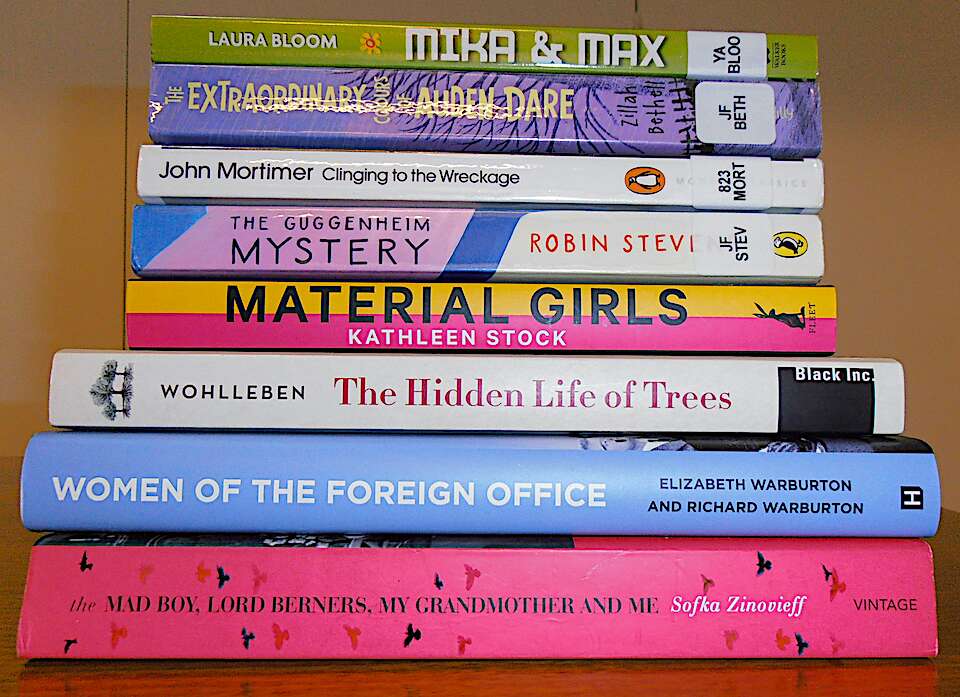

I then read a lovely book about trees. Finally, I read the first volume of John Mortimer’s very unreliable memoir,

Finally, I read the first volume of John Mortimer’s very unreliable memoir,