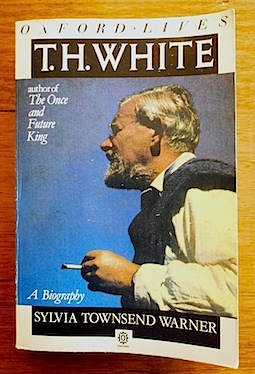

It took me a while to read this excellent biography of the author of The Once and Future King – not because it was lengthy or written in ‘difficult’ prose (quite the contrary), but because it often made me sad and I kept needing to put it down to have a bit of a think about what I’d read. Terence Hanbury White had an awful childhood – born in India in 1906 to feuding parents who frequently threatened to shoot one another, and him, and who then bitterly separated in an era when divorce was a great scandal. His father abandoned the family, and his mother alternately smothered and maltreated her only child. White was sent to a sadistic English boarding school, then worked as a private tutor until he had enough money to put himself through Cambridge, with his studies interrupted by a life-threatening bout of tuberculosis. After achieving a First Class with Distinction, he worked as a schoolmaster for a few years, then spent the rest of his life writing, interspersed with various short-lived enthusiasms – for hunting, fishing, falconry, gardening, flying aeroplanes, sailing yachts, making documentary films about puffins, learning everything there was to know about Irish Catholicism or Arthurian mythology or the Emperor Hadrian …

But as passionate as he was about facts and technical skills, he was not very interested in most people (“How restful it would be if there were no human beings in the world at all”) and he lived a hermit-like existence in various remote cottages for many years. His friend John Verney (author of Friday’s Tunnel), who wrote the introduction to this biography, noted that, “With strangers he could be quite odious; rude and suspicious if he thought they were lionizing him, still more so if he thought they weren’t; shouting down anyone who disagreed with his more preposterous assertions or even ventured to interrupt.” White himself admitted he was “a sort of Boswell, boasting, indiscreet, ranting, rather pathetic” and admitted to “trying to shock people” (to repel them?), although he also had very old-fashioned ideas about modesty, women and sex. Another writer friend, David Garnett, accused White of having a “medieval monkish attitude” and White didn’t disagree. He wrote to Garnett, “I want to get married … and escape from all this piddling homosexuality and fear and unreality.” He tried to fall in love with a barmaid who had a “boyish figure” but this was unsuccessful, as was a later engagement to another young woman. She (sensibly) called it off; he wrote her anguished letters, but his biographer says “his torment in so desperately wanting something he had no inclination for is unmistakable”. He tried psychoanalysis and “hormone therapy” as a cure for homosexuality, which also didn’t work; then he tried to blot everything out with alcohol (“I used to drink because of my troubles, until the drink became an added trouble”). Unfortunately, he wasn’t attracted to men (which would have been bad enough at a time when homosexuality was illegal) but to boys, and he spent years obsessing over a boy called Zed:

But as passionate as he was about facts and technical skills, he was not very interested in most people (“How restful it would be if there were no human beings in the world at all”) and he lived a hermit-like existence in various remote cottages for many years. His friend John Verney (author of Friday’s Tunnel), who wrote the introduction to this biography, noted that, “With strangers he could be quite odious; rude and suspicious if he thought they were lionizing him, still more so if he thought they weren’t; shouting down anyone who disagreed with his more preposterous assertions or even ventured to interrupt.” White himself admitted he was “a sort of Boswell, boasting, indiscreet, ranting, rather pathetic” and admitted to “trying to shock people” (to repel them?), although he also had very old-fashioned ideas about modesty, women and sex. Another writer friend, David Garnett, accused White of having a “medieval monkish attitude” and White didn’t disagree. He wrote to Garnett, “I want to get married … and escape from all this piddling homosexuality and fear and unreality.” He tried to fall in love with a barmaid who had a “boyish figure” but this was unsuccessful, as was a later engagement to another young woman. She (sensibly) called it off; he wrote her anguished letters, but his biographer says “his torment in so desperately wanting something he had no inclination for is unmistakable”. He tried psychoanalysis and “hormone therapy” as a cure for homosexuality, which also didn’t work; then he tried to blot everything out with alcohol (“I used to drink because of my troubles, until the drink became an added trouble”). Unfortunately, he wasn’t attracted to men (which would have been bad enough at a time when homosexuality was illegal) but to boys, and he spent years obsessing over a boy called Zed:

“I am in a sort of whirlpool which goes round and round, thinking all day and half the night about a small boy … The whole of my brain tells me the situation is impossible, while the whole of my heart nags on … What do I want of Zed? – Not his body, merely the whole of him all the time.”

He never told Zed of his true feelings, or acted on them (“I love him for being happy and innocent, so it would be destroying what I loved”), but Zed’s parents grew wary and eventually the boy himself broke off contact. To further complicate matters, White told Garnett that he (White) had managed to destroy every relationship he started because he was a sadist and “the sadist longs to prove the love which he has inspired, by acts of cruelty – which naturally enough are misinterpreted by normal people … if he behaved with sincerity, and instinctively, he alienated his lover and horrified and disgusted himself.” Whether White actually acted on his “sadistic fantasies” is unknown (he had a great talent for self-dramatising and might have been trying to shock Garnett), but he blamed it all on his mother and his boarding school experiences.

The greatest love of his life, though, was Brownie, his red setter. She slept in his bed, was fed elaborate meals, wore a custom-made coat and accompanied him everywhere. (There’s a photo here of Brownie with White, the two of them looking as though they’re posing for a formal engagement portrait.) Brownie eventually became as eccentric as her human:

“She used to kidnap chickens and small animals and keep them as pets, and insisted on taking her pet rabbit to bed with her – in White’s bed. The rabbit bit him freely, but he submitted. She had geological interests, too, and collected stones which she kept under the kitchen table.”

When she died, he sat with her corpse for two days, then at her grave for a week, wrote her an anguished love poem, and forever after kept a lock of her hair in his diary, next to her photo.

White seems to have been a mass of unhappy contradictions. He railed against the British Labour government because he hated paying tax, and he moved to Ireland, then the Channel Islands, to avoid taxes, but he could be very generous with his money and time when it came to charitable causes. He claimed to hate people, but hosted week-long parties at his house in Alderney each summer and his friends all seemed to love him, despite his many faults. He was often miserable, but was “always capable of being surprised by joy” and his writing is full of humour. He announced in his forties that he was done with “forcing myself to be normal” and he gave up drinking – but not for very long, and he died at the relatively young age of fifty-seven of coronary heart disease, probably exacerbated by his drinking and chain-smoking.

This biography includes a discussion of each of White’s books, but I don’t think you need to be familiar with his work to find this book fascinating. I’d only read The Sword in the Stone (which I liked because it was full of animals), but I’m now curious about The Elephant and the Kangaroo, a satire set in Ireland. White, according to his Cambridge tutor, was “far more remarkable than anything he wrote” and his biographer seems to have agreed.

by most of their subjects and all of the press. Nowadays, of course, we’re used to the British royals exposing themselves (in various unflattering ways) in newspapers and on television, but at the time, the Queen Mother was furious at ‘Crawfie’, as the governess was known, for breaking the code of silence that surrounded the royals and as a result, poor old Crawfie was ostracised

by most of their subjects and all of the press. Nowadays, of course, we’re used to the British royals exposing themselves (in various unflattering ways) in newspapers and on television, but at the time, the Queen Mother was furious at ‘Crawfie’, as the governess was known, for breaking the code of silence that surrounded the royals and as a result, poor old Crawfie was ostracised And finally, a novel written by an Elizabeth – Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont by Elizabeth Taylor (the English novelist, not the Hollywood star, although the novelist frequently had to deal with people who’d confused her with the actress). This is a brilliant, but bleak, look at ageing and death in genteel English society in late 1960s London. Elderly Mrs Palfrey is not rich enough to stay in her own home with servants to look after her, not poor enough to move into a state-assisted home for the elderly, and not ill enough for a private hospital or nursing home, but is too polite and independent to impose herself on her middle-aged daughter in Scotland, so she decides to set herself up in a respectable London hotel to wait out her final years. There she meets the other permanent residents, including bitter, arthritic Mrs Arthbuthnot; dim, timid Mrs Post; Mr Osmond, who keeps himself busy writing outraged letters to the newspapers and telling disgusting jokes to the waiters; and mauve-haired, drunken Mrs Burton (named, according to one review I read, after the actress). When she has a fall in the street, Mrs Palfrey is rescued by a young, impoverished writer called Ludo, which leads to a strange sort of friendship between them. Each is using the other – Mrs Palfrey now has a handsome, charming ‘grandson’ to show off to the hotel residents and someone to make her feel needed, while Ludo gains a more satisfactory ‘mother’ than his real mother, and also accumulates a lot of useful material for the novel he’s writing (about old people living at a hotel, entitled They Weren’t Allowed To Die There). Elizabeth Taylor’s observations of character are astute and very funny but also very sad. The residents are all bored, lonely and frightened, but feel unable to admit to this, let alone try to help themselves, so they spend their days obsessing over the hotel menus, spreading spiteful gossip, and complaining about modern life. The author has been called a twentieth-century Jane Austen and for once, that’s not an exaggeration. Mrs Post, for example, is described as “too vague, too bird-brained to achieve real kindness. She had always meant well – and it was the thing people most often said about her – but had managed very seldom to help anyone”, while snobby Lady Swayne manages to irritate even mild-mannered Mrs Palfrey, with “all of [Lady Swayne’s] most bigoted or self-congratulatory statements prefaced with ‘I’m afraid’. I’m afraid I don’t smoke. I’m afraid I’m just common-or-garden Church of England. (Someone had just mentioned Brompton Oratory.) I’m afraid I’d like to see the Prime Minister hanged, drawn and quartered. I’m afraid I think the fox revels in it. I’m afraid I don’t think that’s awfully funny.” I won’t provide any plot spoilers, but I will say that if you’re hoping for a sweet, sentimental look at old age, this is not the book for you. I loved it, but it was rather depressing. And now I’m off to find some more Elizabeth Taylor novels to read.

And finally, a novel written by an Elizabeth – Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont by Elizabeth Taylor (the English novelist, not the Hollywood star, although the novelist frequently had to deal with people who’d confused her with the actress). This is a brilliant, but bleak, look at ageing and death in genteel English society in late 1960s London. Elderly Mrs Palfrey is not rich enough to stay in her own home with servants to look after her, not poor enough to move into a state-assisted home for the elderly, and not ill enough for a private hospital or nursing home, but is too polite and independent to impose herself on her middle-aged daughter in Scotland, so she decides to set herself up in a respectable London hotel to wait out her final years. There she meets the other permanent residents, including bitter, arthritic Mrs Arthbuthnot; dim, timid Mrs Post; Mr Osmond, who keeps himself busy writing outraged letters to the newspapers and telling disgusting jokes to the waiters; and mauve-haired, drunken Mrs Burton (named, according to one review I read, after the actress). When she has a fall in the street, Mrs Palfrey is rescued by a young, impoverished writer called Ludo, which leads to a strange sort of friendship between them. Each is using the other – Mrs Palfrey now has a handsome, charming ‘grandson’ to show off to the hotel residents and someone to make her feel needed, while Ludo gains a more satisfactory ‘mother’ than his real mother, and also accumulates a lot of useful material for the novel he’s writing (about old people living at a hotel, entitled They Weren’t Allowed To Die There). Elizabeth Taylor’s observations of character are astute and very funny but also very sad. The residents are all bored, lonely and frightened, but feel unable to admit to this, let alone try to help themselves, so they spend their days obsessing over the hotel menus, spreading spiteful gossip, and complaining about modern life. The author has been called a twentieth-century Jane Austen and for once, that’s not an exaggeration. Mrs Post, for example, is described as “too vague, too bird-brained to achieve real kindness. She had always meant well – and it was the thing people most often said about her – but had managed very seldom to help anyone”, while snobby Lady Swayne manages to irritate even mild-mannered Mrs Palfrey, with “all of [Lady Swayne’s] most bigoted or self-congratulatory statements prefaced with ‘I’m afraid’. I’m afraid I don’t smoke. I’m afraid I’m just common-or-garden Church of England. (Someone had just mentioned Brompton Oratory.) I’m afraid I’d like to see the Prime Minister hanged, drawn and quartered. I’m afraid I think the fox revels in it. I’m afraid I don’t think that’s awfully funny.” I won’t provide any plot spoilers, but I will say that if you’re hoping for a sweet, sentimental look at old age, this is not the book for you. I loved it, but it was rather depressing. And now I’m off to find some more Elizabeth Taylor novels to read. The ‘Leopard’ is Don Fabrizio, the head of an ancient noble family of Sicily in 1860, which is not a very good time to be a Sicilian prince. Should Don Fabrizio continue to prop up the disintegrating Kingdom of the Two Sicilies or should he support Garibaldi and his Red Shirts as the rebels attempt to unify Italy? Don Fabrizio’s handsome, charming nephew, Tancredi, has no doubts. “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change,” declares Tancredi. Then he rushes off to join the Red Shirts, gains a heroic (but not very serious) wound, and swaggers back to the family’s country estate, where he falls in love with the mayor’s beautiful daughter, to his cousin Concetta’s dismay. A further dilemma for Don Fabrizio! Should he permit, even encourage, this marriage? The mayor, Don Calogero, is vulgar, devious and violent, the very opposite of a nobleman, but he’s rich and powerful and the marriage would allow ambitious Tancredi to prosper in this new regime. But what about poor Concetta’s broken heart? Will she continue to spurn Tancredi’s friend, the shy but devoted Count? Will the hapless family priest, Father Pirrone, ever manage to convince Don Fabrizio to take religion seriously? Will Paolo, Don Fabrizio’s useless son, ever turn into a worthy heir? And will Bendicò, Don Fabrizio’s affectionate but destructive Great Dane, ever stop digging up the flower beds?

The ‘Leopard’ is Don Fabrizio, the head of an ancient noble family of Sicily in 1860, which is not a very good time to be a Sicilian prince. Should Don Fabrizio continue to prop up the disintegrating Kingdom of the Two Sicilies or should he support Garibaldi and his Red Shirts as the rebels attempt to unify Italy? Don Fabrizio’s handsome, charming nephew, Tancredi, has no doubts. “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change,” declares Tancredi. Then he rushes off to join the Red Shirts, gains a heroic (but not very serious) wound, and swaggers back to the family’s country estate, where he falls in love with the mayor’s beautiful daughter, to his cousin Concetta’s dismay. A further dilemma for Don Fabrizio! Should he permit, even encourage, this marriage? The mayor, Don Calogero, is vulgar, devious and violent, the very opposite of a nobleman, but he’s rich and powerful and the marriage would allow ambitious Tancredi to prosper in this new regime. But what about poor Concetta’s broken heart? Will she continue to spurn Tancredi’s friend, the shy but devoted Count? Will the hapless family priest, Father Pirrone, ever manage to convince Don Fabrizio to take religion seriously? Will Paolo, Don Fabrizio’s useless son, ever turn into a worthy heir? And will Bendicò, Don Fabrizio’s affectionate but destructive Great Dane, ever stop digging up the flower beds?

and

and  These books provided a delightful distraction during my recent lengthy convalescence, so I feel obliged to gush about them here, even though you’re probably already familiar with them. Actually, why hadn’t I read them before? They are exactly my cup of tea – comedies of manners, set in England during the 1920s and 1930s, mercilessly poking fun at the trivial pursuits and snobbery of the idle rich. Few of the characters are likeable, but that just makes their frantic attempts to clamber to the top of the social pile all the more entertaining. The queen of their society is Emmeline ‘Lucia’ Lucas, whom even her loyal friend Georgie describes as

These books provided a delightful distraction during my recent lengthy convalescence, so I feel obliged to gush about them here, even though you’re probably already familiar with them. Actually, why hadn’t I read them before? They are exactly my cup of tea – comedies of manners, set in England during the 1920s and 1930s, mercilessly poking fun at the trivial pursuits and snobbery of the idle rich. Few of the characters are likeable, but that just makes their frantic attempts to clamber to the top of the social pile all the more entertaining. The queen of their society is Emmeline ‘Lucia’ Lucas, whom even her loyal friend Georgie describes as I was intrigued to see how few of the characters fitted into the traditional married-with-children mould, and the most endearing characters were all coded as gay or lesbian. Irene, for instance, has an Eton crop, wears men’s clothes and lives with her not-very-servant-like maid, Lucy. Meanwhile, Georgie is obsessed with his appearance and his favourite hobbies are embroidery and watercolour painting (and Major Benjy sneeringly refers to him as “Miss Milliner Michael-Angelo”). There’s no indication that Georgie is attracted to men – in fact, he spends all his time in the company of women and is devoted to Lucia – but he has a panic attack whenever it seems that a woman might be attracted to him and he eventually settles into a happy, celibate marriage with Lucia. The novels have also been described as abounding in “camp humour”, so it did not surprise me to learn that E. F. Benson was “

I was intrigued to see how few of the characters fitted into the traditional married-with-children mould, and the most endearing characters were all coded as gay or lesbian. Irene, for instance, has an Eton crop, wears men’s clothes and lives with her not-very-servant-like maid, Lucy. Meanwhile, Georgie is obsessed with his appearance and his favourite hobbies are embroidery and watercolour painting (and Major Benjy sneeringly refers to him as “Miss Milliner Michael-Angelo”). There’s no indication that Georgie is attracted to men – in fact, he spends all his time in the company of women and is devoted to Lucia – but he has a panic attack whenever it seems that a woman might be attracted to him and he eventually settles into a happy, celibate marriage with Lucia. The novels have also been described as abounding in “camp humour”, so it did not surprise me to learn that E. F. Benson was “