A few years ago, I stopped working at a Proper Job* and on my final day, my colleagues had a little party and presented me with a farewell gift – a lovely silver pen and a blank journal. I’d just had my first novel accepted for publication and my colleagues said I could use the pen and book to write my next novel. It was a lovely idea, and in fact, I did use the pen to take notes for A Brief History of Montmaray (and indeed, I still use that pen nearly every day, because it really is a very nice pen, of exactly the right size and weight and ink colour to suit my tastes). But as for the blank journal – well, I type my novels on a computer, and when I take research notes, they’re scribbled on cheap lecture pads and technicoloured Post-It notes. I couldn’t imagine writing a novel (with all the crossing-out and page-tearing-out that that involves) in a beautiful journal with gilt-edged pages, decorated with a detail from a Charles Rennie Mackintosh painting**.

The book was simply too pretty to sully with my scribblings, so it sat in a cupboard for a couple of years.

However, at the start of 2011, I decided it would be handy to keep a record of all the books I read and to make brief notes on the books I found interesting (either interestingly good or interestingly bad). I suppose I could have just joined Goodreads or LibraryThing, as everyone else does, but I wanted to keep my notes private. I considered setting up some sort of spreadsheet on my computer, but that sounded too much like hard work. And then I remembered my ‘Blank Note Book’.

Readers, it is blank no more.

Note: Photo is artfully blurred so you can’t see what I wrote about Insignificant Others and Dead Until Dark – although I did enjoy both those books, for different reasons.

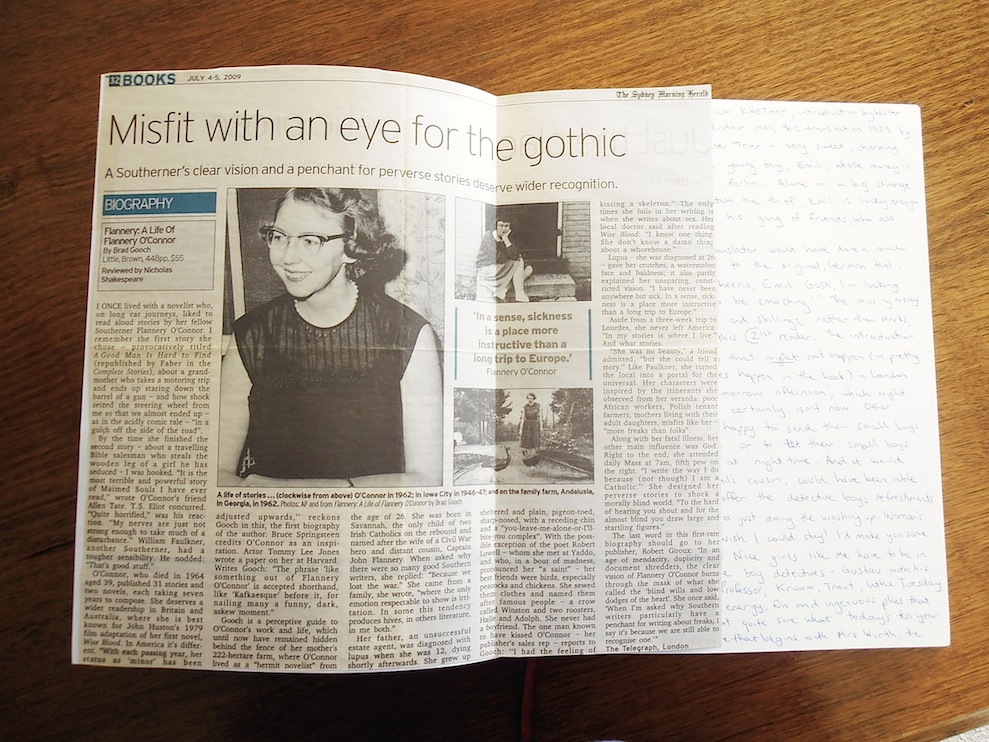

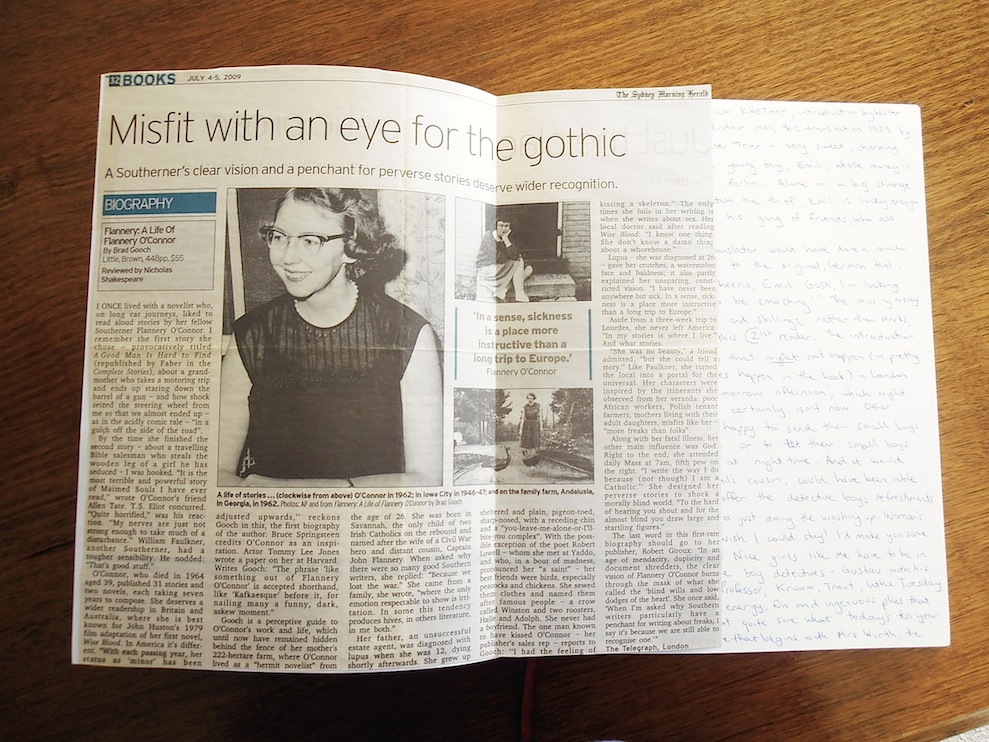

I write down the title and author of each book I read and what I thought of the book. Sometimes I only write a sentence; sometimes I write pages. I often write about the book’s structure and the effectiveness of the literary devices used, because analysing other books helps me to become a better writer. But just as often, my book journal reflects how I was feeling and what was going on in my world at the time I read the book, so I guess it is a bit like a personal diary. The books I really loved get a star, and I use the stars to compile my Favourite Books blog post at the end of each year. Sometimes I also stick in the review that prompted me to try the book in the first place.

At the front of my journal, I keep clippings of book reviews and Post-It notes of titles that have caught my attention. When I start to run out of books to read, I consult these notes and reviews, and track the books down at the library or the bookstore (usually the library, because I am now an impoverished writer lacking a Proper Job). My current To Be Tracked Down book list includes:

The Uninvited Guests by Sadie Jones

A Few Right Thinking Men by Sulari Gentill

Cold Light, the final book in the Edith Campbell Berry trilogy, by Frank Moorehouse

Backwater War by Peggy Woodford

Lettie Fox by Christina Stead

A Pattern of Islands by Arthur Grimble

There are also quite a few books on my list that have not been treated to very much investigation at all. For example, I have a Post-It note that says ‘Hilary McKay – Casson family?’, which means I haven’t actually got around to looking up the book titles, let alone reserving them from the library. I also got stuck on Patrick Melrose’s novels, because the library catalogue informed me it only had the fourth book in a five-book series. (Does anyone know if I need to read Never Mind/Bad News/Some Hope before Mother’s Milk? Or are the books so depressing that I’ll regret reading any of them?) Still, it’s not as though I have a dearth of reading material at the moment.

Now that I’ve started a book journal, I wish I’d kept a record of all the books I’d ever read. It would be fascinating to see what I thought of The Famous Five and Trixie Belden and What Katy Did and all those other books I loved to pieces (literally) in my early reading years. Or maybe it would just be really embarrassing.

* That is, a job which involved me commuting by train to an office, often while wearing a suit, and having someone else pay me each fortnight and even pay me when I went on holiday or got sick . . . Oh, those were the good old days.

** It’s a detail from Part Seen, Imagined Part (1896), which apparently can be viewed at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow.

*** One day I will figure out how to do proper footnotes in WordPress.

For those of you who keep book journals, I’d also like to remind you that my book giveaway is still open, till the end of the month. You could win a copy of the Vintage Classics edition of A Brief History of Montmaray and then write about it in your journal! (Note: Those who don’t have book journals are also welcome to enter the giveaway.)

(The Alice who has Adventures in Wonderland, that is.) I’ve written a blog post about why I love Alice here to celebrate the release of the new Vintage Classics edition of this utterly brilliant book.

(The Alice who has Adventures in Wonderland, that is.) I’ve written a blog post about why I love Alice here to celebrate the release of the new Vintage Classics edition of this utterly brilliant book.