Yesterday, I posted some photographs of a Lion and a Unicorn. Here’s where they live:

They’re over the southern entrance to the Main Quadrangle of the University of Sydney, which is Australia’s oldest university. On the left side of the photo you can see part of MacLaurin Hall, the original university library. Here’s another view of MacLaurin Hall:

I sat for exams in that building a couple of decades ago. (I blame the extremely distracting neo-Gothic architectural details for my poor results.)

If you walk through the Lion and the Unicorn entrance, you’ll find yourself in the Main Quadrangle, which features a beautiful jacaranda tree:

The tree is covered in vivid purple flowers in late spring. It’s said that if you haven’t started studying by the time the jacaranda flowers, you’ll fail all your exams. Here’s another view of the Main Quad, showing the Clock Tower and Carillon:

According to Tess van Sommers, who wrote the text of University of Sydney Sketchbook, “If architect Edmund Blacket had had his way, this tower would have had even more ornate turrets than it has now; some almost deliriously convoluted pinnacles were among his rejected designs.”

At the left side of the photo, you can see a bit of the Great Hall, a “scaled-down version of Westminster Hall in London”. At the moment, most of it is covered in scaffolding, so I didn’t take a photo from the front, but it’s a fairly spectacular edifice. Apparently, its construction in the 1850s and 1860s did not go smoothly, with workmen often abandoning the site to join the latest gold rush, while politicians kept raising doubts about “the need for such frivolities as gargoyles”. Also, “for some years, the frontal majesty of the block was marred by an approach through cow pastures” and what is now Victoria Park featured a dam in which horses bathed and occasionally died.

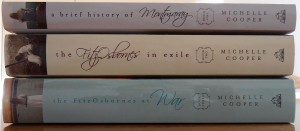

But what, you may ask, does all this have to do with my current writing project? Good question. I don’t have a very detailed answer yet, but wait and see. It’s possible that something interesting and historical and book-shaped will (eventually) appear.

When I read fiction, I like to read about characters who are interesting. If I don’t care about them, why should I keep reading to find out what happens to them? Sometimes I find characters interesting because they’re likeable, but other characters are interesting because they’re absolute monsters. For example, I love Mrs Proudie in Barchester Towers and Lady Montdore in Love in a Cold Climate – their very awfulness provides most of the comedy in those novels. My favourite example of an unlikeable narrator is Barbara in Zoë Heller’s Notes on a Scandal. There is no way I’d ever want to be Barbara’s friend, or even work in the same place as her, but her shrewd observations and general misanthropy make her wickedly perfect for her role in that novel.

When I read fiction, I like to read about characters who are interesting. If I don’t care about them, why should I keep reading to find out what happens to them? Sometimes I find characters interesting because they’re likeable, but other characters are interesting because they’re absolute monsters. For example, I love Mrs Proudie in Barchester Towers and Lady Montdore in Love in a Cold Climate – their very awfulness provides most of the comedy in those novels. My favourite example of an unlikeable narrator is Barbara in Zoë Heller’s Notes on a Scandal. There is no way I’d ever want to be Barbara’s friend, or even work in the same place as her, but her shrewd observations and general misanthropy make her wickedly perfect for her role in that novel.