Way back in 2012, I wrote this on Memoranda, in response to a reader’s question:

“Shannon asked me about the new book I’m working on, so I composed a long blog post on the subject, complete with jokes and a cool photograph of a turtle. But then I read over it and realised I didn’t feel comfortable revealing that much detail about a writing project that’s at such an early stage, it doesn’t even have a title, let alone a publisher.

So I deleted the post.

But it wasn’t a complete waste of time, because I also realised that writing that post had made me feel more confident about this new book. After I finished ‘The FitzOsbornes at War’, I flipped through my mental catalogue of Ideas For Books and decided I needed to write something that would not be the start of a series, would not be a complicated family saga, would not include scenes of heart-rending anguish, and would not require much research. This next book would be fun and easy to write!

Of course, it hasn’t turned out quite the way I’d expected. I’ve spent the past six months compiling a vast folder of notes and diagrams and photocopies, but feel I’ve barely started on the research. It isn’t a complicated family saga, but at the heart of the story is a mystery that requires far more complicated plotting than I’ve ever before attempted. It was supposed to be a stand-alone novel, but I already have ideas for a sequel and I’m not even sure the book would be best described as a ‘novel’. Plus, there’s at least one scene of heart-rending anguish…”

And five years on, I’m still working on that book, although at least now, I know what it’s about.

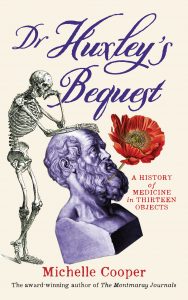

Dr Huxley’s Bequest grew out of several ideas. One of them was sparked by my irritation at shoddy articles about health and medicine in supposedly reputable newspapers. One particular Australian journalist, who clearly had no scientific education whatsoever, specialised in what I came to think of as ‘blueberries cure cancer’ stories – that is, articles that misrepresented or ignored scientific research in favour of sensational, fact-free assertions by celebrities and self-proclaimed experts who had no medical qualifications. I have a science degree and have worked in health sciences for most of my adult life, so I could see these articles were utter rubbish, but what about other readers? People were spending lots of money on these useless ‘cures’ and sometimes putting their health at risk by following harmful advice.

I was especially concerned about teenagers who dropped science subjects early in high school because they hated maths or decided science was boring or difficult. Scientific literacy is just as important in modern life as being able to read and write and interact socially. Science doesn’t always have to be learned in a classroom, though. Some of my favourite reads in recent years have been popular science books – books written by experts who are good at explaining complex scientific ideas in an entertaining and informative way. But those books are all aimed at adults. Where are the popular science books for teenagers, especially teenage girls?

It’s not that there are no Australian books about science for young readers. There are thousands of colourful, interesting books for primary school students on a wide variety of science topics, from astronomy to zoology. There are science books for older students, too. There are well-written and well-designed text books used by science teachers in the classroom, but they’re not intended for general reading. I’ve also seen books with eye-catching titles and cartoon covers, along the lines of There’s a Worm on My Eyeball!, full of disgusting facts and clearly marketed at boys.

Of course, there’s nothing to stop girls picking up these books and some girls do like them, but I was interested in writing something more thoughtful and philosophical, although still entertaining – a book that would appeal to teenage girls who were interested in history and stories and people, but thought science was difficult, dull and only for boys. I decided a history of medicine, from superstition to science, might be a good way to introduce the beauty, creativity and power of scientific thinking. The book needed a framing narrative, so I came up with Rosy and Jaz, two very different thirteen-year-old girls who are thrown together one summer holiday because their parents work at the same college. A mysterious bequest sends Rosy and Jaz on a race against time to identify thirteen strange and wonderful artefacts – which turn out to tell the story of medicine, from the superstitions of ancient Egypt to the ethical dilemmas of genetic testing.

Rosy and Jaz find themselves arguing with Hippocrates, Aristotle and Galen, being horrified by the Black Death, body-snatching and eighteenth-century surgical techniques, and scrutinizing modern homeopathy and the anti-vaccine movement. They uncover the secrets of the brain’s anatomy in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel paintings, and find a link between herbal medicine and Vincent Van Gogh’s masterpieces. They learn how the discovery of penicillin demonstrated the benefits of having an untidy desk, why an Australian scientist thought it would be a good idea to drink dangerous bacteria, and how traditional Aboriginal remedies might save lives when modern antibiotics fail. And there’s more:

What does aspirin have to do with secret agents, revolution, stolen treasures and explosions?

Can unicorns cure leprosy?

Who thought it was a good idea to use heroin as a cough medicine for children?

Is grapefruit evil?

Did a zombie discover the cure for scurvy?

Does acupuncture really work?

Did the bumps on Ned Kelly’s head predict his fate?

And how exactly did parachuting cats save a village from the plague?

It’s a little bit like Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder, but about the history of medical science rather than the history of philosophy. (Incidentally, whenever I said this to publishers, I got blank looks. How can you work in the publishing industry and not have heard of Sophie’s World?! It was an international best-seller! It won awards! It was made into a film and a TV series and even a computer game! And by the way, it was the reason the narrator of the Montmaray Journals was called ‘Sophie’.)

Anyway, this is how Dr Huxley’s Bequest starts:

CHAPTER ONE

Afterwards, Rosy always blamed the turtle.

‘It wasn’t the turtle’s fault,’ said Jaz, as the two girls sat in the courtyard beside the pond, eating salt-and-vinegar chips.

‘You weren’t there, Jaz. You didn’t see his evil expression. He knew exactly what he was doing. None of it would have happened without that turtle.’

The turtle in question raised his head and turned his beady yellow gaze upon them.

‘Look,’ said Rosy. ‘He’s doing it again. Malevolent, that’s what I call him.’

‘How do you know it’s a boy?’

‘He’s got a beard.’

Jaz peered closer. ‘I think that’s a bit of lettuce stuck to its chin.’

‘After all that everyone here’s done for him, too,’ Rosy went on. ‘Feeding him. Cleaning his stupid pond. And how did he repay us? With treachery and disloyalty and, and … dirty tricks! Just imagine the disaster that would have befallen this college if we hadn’t come to the rescue.’

‘Well, considering there wouldn’t have been a problem if you hadn’t –’

‘Malicious,’ Rosy said quickly. ‘That’s what he is. Mephistophelean.’

‘That is not even a word.’

‘It is. It’s from Mephistopheles. Remember, that stone demon spitting into the fountain in Science Road?’

‘Oh, right,’ said Jaz. ‘Faust. The quest for knowledge.’

‘Exactly,’ said Rosy.

The turtle lunged at a passing dragonfly, snapping off its wing and a couple of legs. The unfortunate insect tumbled onto the surface of the pond and the turtle gulped it down, then twisted his wrinkled, serpentine neck in the direction of the girls.

‘He does look a bit sinister,’ Jaz conceded.

Text and illustration © Michelle Cooper

More in Adventures in Self-Publishing:

Why Self-Publish?

Editing

To Tweet Or Not To Tweet

Designing a Book Cover

Turning Your Manuscript Into A Book

All the Mistakes I’ve Made (so Far)

I’ve updated my website with an excerpt of my new book, Dr Huxley’s Bequest.

I’ve updated my website with an excerpt of my new book, Dr Huxley’s Bequest.