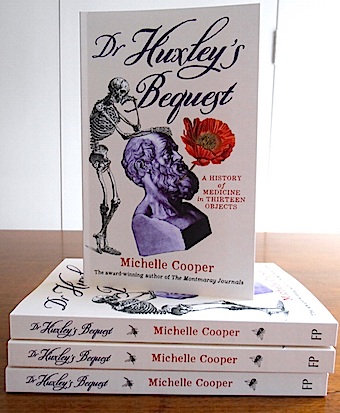

There’s a new paperback edition of Dr Huxley’s Bequest out tomorrow, Monday 15 January. This new edition has exactly the same content as the first edition, but the print size has been increased slightly (so it has 342 pages, rather than 270). I think the larger print will make it more enjoyable to read, especially for younger readers. This is how the new paperback looks:

And there are illustrations inside:

Dr Huxley’s Bequest is also available in various ebook formats.

Wait, I have only just heard of this book. What’s it about?

Dr Huxley’s Bequest is a history of medicine for thoughtful readers aged about 12+, in the form of a mystery story, full of jokes and fascinating facts. It’s also a thoughtful look at the beauty, creativity and power of scientific reasoning and it’s especially for girls (particularly girls who’ve been told science is difficult, dull and only for boys).

You can read an excerpt of the book here and read more about the book’s real-life setting here. If you’d like to know more about why I wrote the book, see this blog post.

Which edition of Dr Huxley’s Bequest should I buy?

This second edition paperback has illustrations, author notes, a bibliography, a comprehensive index and a pretty cover. The first edition paperback is now out of print. (If you’d like to know why there’s a second edition coming out just two months after the first edition was published, see this very long blog post.)

The ebook versions are available in two formats. There’s a Kindle (mobi) version for Kindle readers and other devices that have the Kindle app installed. There’s also an ePub version, for iPads, iPhones, Nook readers, Kobo readers, and pretty much every other sort of ebook reading device. The ebooks don’t have the illustrations or the index, but do include the author notes and bibliography and they have a search function if you want to find keywords.

Where can I buy the book?

Here are some of the places where you can buy Dr Huxley’s Bequest online. I’ve listed stockists according to geographical region, because delivery costs are cheaper and you won’t have to pay currency conversion fees if you buy locally.

Australia and NZ

Amazon.com.au (paperback, Kindle ebook)

Angus & Robertson Bookworld (paperback, ePub ebook)

Apple iBooks (iBook ebook)

Booktopia (paperback)

Fishpond (paperback)

Kobo (Kobo ebook)

North America

Amazon.com (paperback, Kindle ebook)

Apple iBooks (iBook ebook)

Barnes & Noble (paperback, Nook ebook)

Chapters/Indigo Canada (Kobo ebook)

Kobo (Kobo ebook)

UK and Europe

Adlibris (paperback)

Amazon.co.uk (paperback, Kindle ebook)

Apple iBooks (iBook ebook)

Book Depository (paperback)

Foyles (paperback)

Kobo (Kobo ebook)

Libris (ePub ebook)

Waterstones (paperback)

Will it be in my local bookshop?

Maybe, if you ask them to order it for you! Bookshops are often reluctant to stock books that are self-published or published by small publishers. However, all book retailers will receive the same trade discount for this book as when they buy books from large publishers and any unsold books are returnable. Booksellers can order the book from Ingram Spark. (For more information, including ISBNs, see FitzOsborne Press.)

Can I borrow it from my library?

Maybe, if you live in Australia. If it’s not in your library’s catalogue, you can ask your librarian to order it. The book is in the catalogue of ALS Library Services and it has a National Library of Australia cataloging number.

Anything else I should know?

Dr Huxley’s Bequest is also on Goodreads, if you’d like to leave a review. (Thank you, Tina!)