The book I’m currently trying to write is set in my neighbourhood, which is a new experience for me. If I needed to know the details of a particular location when I was writing the Montmaray books, I either had to make it up from scratch or travel through time and space in my TARDIS1 to examine the place. Now, though, I can simply go for a short walk down the road and take a few photos.

This saves a lot of time and effort, but I’ve also become aware of how much I’m editing my setting. For example, I’m deleting the graffiti and most of the roadside litter and that ugly sixties office block on the corner, and concentrating instead on the lovely Victorian and Art Deco architecture and the manicured cricket pitch and all the majestic old trees. When (if?) I ever finish writing the book, I plan to draw a map, so that readers can walk along the same streets as my characters and visit the same buildings2. But while my book’s setting is ‘true’ for the most part, it’s certainly not the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

I was thinking about this because a while back, I saw an American blogger3 exclaim that, thanks to Melina Marchetta‘s novels, the blogger now knew exactly what the inner western suburbs of Sydney were like. And when I read that, I flapped my hands at my computer screen and cried, “No, no, it’s not like that at ALL!” Now, I must admit, Melina Marchetta would probably not classify me as a TRUE Inner Westie. I was not born at King George V Memorial Hospital for Mothers and Babies (although I did once work there, or at least visit it often while I was employed at the adjacent hospital), I’ve only lived in the inner west for about twenty-five years, and (horror of horrors) I don’t drink coffee. On the other hand, I have lived in the same suburbs as Josephine Alibrandi and Francesca Spinelli and Thomas Mackee (in fact, part of Looking for Alibrandi was filmed in my street) and most of the places mentioned in the novels are very familiar to me.

AND YET. Melina Marchetta’s Inner West is not my Inner West. For example, in Melina Marchetta’s Inner West, nearly everyone is of European ancestry, goes to a private school and is Catholic (nominally, not necessarily in an attending-Mass-each-Sunday way). Hardly anyone is Aboriginal Australian or Asian-Australian or Pacific-Islander-Australian. Gay and lesbian people exist only to show how tolerant (or temporarily intolerant) the main characters are. And no one seems to use contraception (and when the inevitable pregnancy results, no one even mentions the possibility of the existence of abortion). Now, of course, there are plenty of heterosexual, pregnant Italian-Australians in the Inner West. But in the ‘real’ (that is, my) Inner West, there are also lots of people without European ancestors. There are lots of atheists. It is true that there are several expensive and/or religious private schools in the area, but nearly all young children go to (fee-free) state primary schools, and among the most prestigious, difficult-to-get-into high schools are two (fee-free) state schools, Fort Street High and Newtown High School of the Performing Arts. Also, a local council survey a few years back found that about 21% of residents identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender. More than one in five people! (Admittedly, the council area did not include Leichhardt and did include some parts of the very gay inner east of Sydney, but I should also point out that the inner west hosts the headquarters of Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, plus a number of gay pubs and clubs; that local businesses routinely stock the free LGBTQ community newspapers and the local cinema hosts Queer Screen; and that Leichhardt used to be known as Dyke-Heart due to the large number of lesbian couples who lived there.) Oh, and Australia’s oldest, most famous, feminist-run women’s health clinic, which used to provide abortion services and still offers abortion counselling, is right in the middle of Leichhardt.

This isn’t to say that Melina Marchetta’s version of the Inner West is ‘wrong’ – in fact, I admire her vivid and evocative snapshots of the places that I know and love. But, as with any snapshot, there’s far more outside the frame than captured within it, and the positioning of the frame itself depends on the person holding the camera. What I need to figure out as I try to write my own book is whether I’m holding my camera up to the most important, useful and authentic scenes, or letting my own unexamined preferences frame each shot.

_____

- I don’t actually have a TARDIS. What I actually had to do was look at lots of old maps and photos and diaries. ↩

- Look, Simmone Howell has done the same for her novel, Girl Defective! ↩

- I honestly can’t remember which blogger, otherwise I’d link to the blog post. ↩

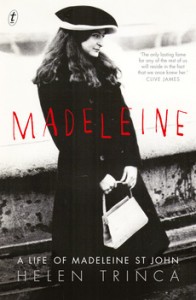

Earlier this year, I enjoyed

Earlier this year, I enjoyed  However, I think Madeleine St John’s novels are even better, and I especially recommend

However, I think Madeleine St John’s novels are even better, and I especially recommend