In my previous discussion of the opening section of The Years of Grace, I neglected the fabulous illustrations, so I’ll make sure to include some here. Each section of this book has an introduction by Noel Streatfeild, and in this second section, ‘Your Home’, she admits that she was a “menace” as a teenager, “scowling round the house, saying ‘Why should I?’ about everything I was asked to do” and bringing home an unsuitably un-English friend called Consuelo (“Girls from Latin countries grow up faster than girls from cold countries. Consuelo probably held the record for fast growing-up even in a Latin country.”).

The first chapter, by Margaret Kennedy, discusses the difficulties of sharing a house with parents and siblings:

“The mother must manage to make room for her daughter’s wider life without letting the others feel that the whole house now belongs to an ENORMOUS GIRL who seems to be everywhere at once – locked in the bathroom when her brother wants to shave, telephoning in the hall at the top of her voice, pressing a dress on the kitchen table and dancing to the radio in the sitting-room.”

(By the way, I thought that illustration’s dense cross-hatched style seemed familiar and it turned out to be the work of John Verney, author of Friday’s Tunnel.)

Margaret Kennedy provides some sensible advice about reaching compromises with parents, including the need to be nice to your parents’ dull old friends (“It is highly mortifying for a mother if the refreshments at her bridge party are brought in by a daughter who looks as though she were dispensing alms to a colony of lepers”) and having to explain your own friends to them (“Parents do not always understand their daughters’ friendships or see where the attraction lies”). This is further explored in an article by Richmal Crompton, who gives useful tips for being a good friend (you need tact, generosity, lack of possessiveness, common but not identical interests, and a shared sense of humour).

Next comes Magdalen King-Hall with a chapter about community service and social justice, even if she doesn’t call it that. Although the examples she provides are a little dated (Elizabeth Fry, William Wilberforce, Florence Nightingale), the message is still relevant today:

“We are linked together, not only with the other people in our own country, but with all the other people in the world. It is like a stone dropped into a pond, the ripples spread out in widening circles – you, your family, your school, your community, your country, your world. This feeling of world citizenship is only in its infancy, but it has been born, and two devastating world wars have not destroyed it.”

She even mentions The League of Nations. Veronica FitzOsborne would approve. But Veronica probably wouldn’t think much of Mary Dunn’s article, ‘The Queen Was in the Kitchen’. Mrs Dunn explains that men reserve their greatest admiration for a girl who can cook:

“Pretty, helpless women are very nice in the fiancée stage, to take to the pictures and to dance with, but after marriage, unless a girl is feminine in the right way, not just to look at but a homemaker, there is going to be trouble. Of course, after he has married her a man still wants a girl to look pretty and to have time to do things with him, but he wants as well to be quite certain that she looks after him better than the wives of all the other chaps in the street, and that he can brag that he is the best-fed man he knows.”

Mrs Dunn despairs because British housewives are letting down the side, compared to their glamorous counterparts in France, Scandinavia and especially the United States. You might think those Hollywood films depicting pretty housewives creating beautiful meals in dazzling kitchens are just Hollywood fantasies. But you would be wrong:

“Most American kitchens are like that and nearly all American girls really are splendid cooks, and really do whisk up superb meals and appear five minutes later in their living rooms looking too glamorous to be true. This business of looking smart when doing housework or cooking is something that we in this country really ought to turn our attention to … I feel sorry for tradesmen; how depressing when they call, to be greeted by a bedraggled object …”

Fortunately, the next article, by Janet Farwell, involved a vet talking to a family about the advantages and disadvantages of various pets (dogs, cats, rabbits, tortoises, fish, hamsters, budgies, silkworms) and included some adorable puppy illustrations, so my blood pressure returned to normal.

Finally, Elizabeth Cadell gave a lot of practical advice on hosting teenage parties, including hints on venues (turn your bedroom into “a very attractive bed-sitting room” by scattering cushions on the floor and covering the dressing table with a tablecloth), refreshments (sausage rolls, trifle, ice-cream, cider cup and “in cold weather, provide Bovril”) and games (cards, Tiddlywinks, charades). Which leads nicely to the next section of The Years of Grace: Leisure.

You might also be interested in reading:

1. The Years of Grace : You

2. The Years of Grace : Your Home

3. The Years of Grace : Leisure

4. The Years of Grace : Sport

5. The Years of Grace : Careers

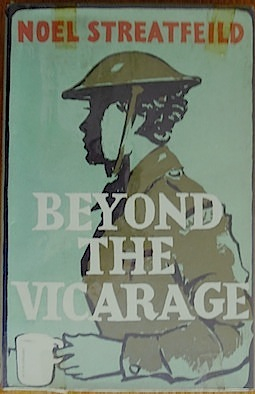

Fair enough, but it does lead to phrases like “Victoria seemed to think that …” and “Victoria must have forgotten that …”, which is a bit odd when she’s writing about herself. Anyway, this book is about how Victoria/Noel decides to stop being a successful actress touring the world and become a writer. She sails back from Australia via Siam (as it was then called), where her brother works, and eventually arrives in England to look after her recently-widowed mother. Although Victoria’s father had been a bishop from a well-off family, the family is now in ‘reduced circumstances’ and Victoria’s mother is the sort of helpless genteel lady who has never had to look after herself, so living in lodgings does not go well. After employing a series of disastrous companions, her mother is finally settled in her own new home with appropriate help and Victoria, breathing a huge sigh of relief, moves back to London to write her first novel. Despite the distractions of her busy social life (she eventually resorts to writing in bed in her pyjamas so she won’t be tempted to go out), she quickly writes the manuscript, immediately finds a publisher and is instantly making a comfortable living as a novelist. Her publisher even pays her a weekly wage when she complains the system of advances and royalties is too complex for her to deal with. The only complaint her publisher has is that “you make everyone too loveable. I doubt you could write about a bitch if you tried.” (Victoria then vows to write “the bitchiest bitch you ever read about” and writes It Pays To Be Good.) Then another publisher, aware of Victoria’s theatrical background, asks her to write a children’s book about child actors, so Victoria, “cross at herself for agreeing to something she was convinced she could not write”, produces Ballet Shoes, which is an instant bestseller, and the rest is history. Although she ended up writing a few more novels for adults, she gave up on them in the early 1960s, telling herself,

Fair enough, but it does lead to phrases like “Victoria seemed to think that …” and “Victoria must have forgotten that …”, which is a bit odd when she’s writing about herself. Anyway, this book is about how Victoria/Noel decides to stop being a successful actress touring the world and become a writer. She sails back from Australia via Siam (as it was then called), where her brother works, and eventually arrives in England to look after her recently-widowed mother. Although Victoria’s father had been a bishop from a well-off family, the family is now in ‘reduced circumstances’ and Victoria’s mother is the sort of helpless genteel lady who has never had to look after herself, so living in lodgings does not go well. After employing a series of disastrous companions, her mother is finally settled in her own new home with appropriate help and Victoria, breathing a huge sigh of relief, moves back to London to write her first novel. Despite the distractions of her busy social life (she eventually resorts to writing in bed in her pyjamas so she won’t be tempted to go out), she quickly writes the manuscript, immediately finds a publisher and is instantly making a comfortable living as a novelist. Her publisher even pays her a weekly wage when she complains the system of advances and royalties is too complex for her to deal with. The only complaint her publisher has is that “you make everyone too loveable. I doubt you could write about a bitch if you tried.” (Victoria then vows to write “the bitchiest bitch you ever read about” and writes It Pays To Be Good.) Then another publisher, aware of Victoria’s theatrical background, asks her to write a children’s book about child actors, so Victoria, “cross at herself for agreeing to something she was convinced she could not write”, produces Ballet Shoes, which is an instant bestseller, and the rest is history. Although she ended up writing a few more novels for adults, she gave up on them in the early 1960s, telling herself, Taking a break from post-war England, I then read Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by US writer,

Taking a break from post-war England, I then read Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by US writer,