This is a gentle, thoughtful novel about friendship, love and change by Rebecca Stead, who won the Newbery Medal for When You Reach Me. I liked this book very much, but also wondered how many middle-grade readers – the intended audience – would persist with it. But I’ll come back to that thought later. Goodbye Stranger is the story of Bridge, a seventh-grader, and her best friends Tabitha and Emily, who all made a vow back in fourth grade to never, ever fight – which proves difficult when their lives seem to be moving in different directions. Bridge was nearly killed in a traffic accident a few years earlier and when not pondering the purpose of her existence (“You must have been put on this earth for a reason, little girl, to have survived,” a nurse told her), she worries whether her friend Sherm “like likes” her, whether her older brother Jamie will ever manage to get rid of his toxic “frenemy” Alex, whether the moon landing was faked, and whether she’ll fail her French class. Meanwhile Tabitha has discovered feminism thanks to her English teacher, Ms Berman (“the Berperson”) and Emily has grown breasts, become the star of the soccer team and is being pursued by older boys.

The plot revolves around a sexting scandal. Why did Emily send a revealing photo of herself to Patrick when she promised Bridge that she wouldn’t? Who sent that photo to all the boys in eighth grade? Does this mean Emily is a “skank”? Should Sherm tell the principal what he knows, even though he’ll be ostracised by the other boys if he does? If Patrick wasn’t responsible, then who is he protecting with his silence? Why does Emily insist on staying loyal to Patrick? And who revenge-posted that revealing photo of Patrick? There’s also a rather confusing subplot set several months into the future, involving an unnamed older teenager responsible for another scandal and narrated in the second person. Other relationships are shown in order to further explore the theme of love – for example, Emily’s parents have divorced but they still go on dates, Sherm’s grandfather has walked out on his wife after fifty years of marriage, and Tab’s mother observes Karva Chauth (when “Good Hindu women fast all day to show their devotion to their husbands”, which Tab thinks is anti-feminist, although her older sister Celeste thinks it’s “romantic”).

The plot revolves around a sexting scandal. Why did Emily send a revealing photo of herself to Patrick when she promised Bridge that she wouldn’t? Who sent that photo to all the boys in eighth grade? Does this mean Emily is a “skank”? Should Sherm tell the principal what he knows, even though he’ll be ostracised by the other boys if he does? If Patrick wasn’t responsible, then who is he protecting with his silence? Why does Emily insist on staying loyal to Patrick? And who revenge-posted that revealing photo of Patrick? There’s also a rather confusing subplot set several months into the future, involving an unnamed older teenager responsible for another scandal and narrated in the second person. Other relationships are shown in order to further explore the theme of love – for example, Emily’s parents have divorced but they still go on dates, Sherm’s grandfather has walked out on his wife after fifty years of marriage, and Tab’s mother observes Karva Chauth (when “Good Hindu women fast all day to show their devotion to their husbands”, which Tab thinks is anti-feminist, although her older sister Celeste thinks it’s “romantic”).

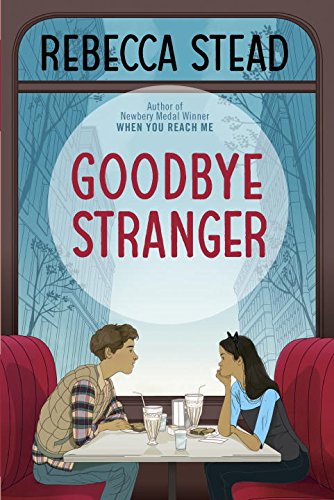

There were a lot of things I liked about this novel. The main characters are smart but realistically flawed and the smartest of them does something very, very stupid, yet somehow plausible. They do things they regret, and then they say sorry, face the consequences and learn something from it. The friendship between the three girls is lovely and I really liked that by the end, they’d realised that ‘No Fights’ doesn’t work very well as a friendship policy. Most of the characters are also really NICE, which was a pleasant change after reading so many YA novels filled with snarky, cynical teenagers. The sibling relationships are great – Bridge and her brother Jamie bond over their shared love of a cheesy Christmas movie; Tab and Celeste have very different interests, yet manage to share a bedroom amicably; Emily (and her friends) care about her odd little brother Evan. The parents, grandparents and teachers are also caring and sensible and I especially liked Mr P, the “intense” teacher who oversees Bridge, Sherm and the other members of Tech Crew and runs a book club for kids with divorced parents. Also, the setting was great! I love reading about New York students who walk home from school to their brownstone houses via the local diner, where they sit in booths and order vanilla milkshakes and cinnamon toast to share. (Possibly New York readers get a similar kick out of reading stories about Australian teenagers riding around their farms on quad bikes and bottle-feeding orphaned kangaroos.) Despite the characters in this novel being very privileged, they’re also ethnically diverse – Bridge’s father is Armenian-American, Sherm’s grandparents migrated from Sicily, Tab and Celeste’s parents came from India via France – but none of this is made into an Issue.

However, some things didn’t work so well for me. I didn’t understand why the Mysterious Narrator chapters had to be in the second person, why the timeline had to diverge from the main plot or why the narrator had to be Mysterious. I found these sections confusing and distracting, and I think the novel could have done without them. In fact, my main criticism of this book was that there was just TOO MUCH going on. While the author is highly skilled, this book is nearly three hundred pages long and her efforts to connect every little subplot and character mean that plausibility is stretched to its limits by the end (for those who’ve read the book, the moment when Bridge realises which yellow VW ‘caused’ her accident was the moment I shouted, “ENOUGH!”). It was this that made me wonder whether the book might be too long, complex and slow-moving for a lot of eleven- and twelve-year-old readers (I should note that the ‘sexting’ parts of the book are very mild – I don’t think they’re too confronting for this age group to read). Some reviewers have also raised this concern – for example, this commenter felt the book “reads just like a contemporary literary novel for adults.” A teacher-librarian on Goodreads believed it would not appeal to her own students and a commenter below her review wondered “if children’s writers are writing for the award committees, rather than the kids”. Meanwhile Elizabeth Bird at School Library Journal, who has served on the Newbery award panel, raves about the book and thinks it’s perfect for middle-graders but acknowledges:

“…were it not for the author’s fantastic writing and already existing fan base, it would languish away in that no man’s land between child and teen fiction. Fortunately Stead has a longstanding, strong, and dedicated group of young followers who are willing to dip a toe into the potentially murky world of middle school.”

I agree with most of these points of view – I think Goodbye Stranger will find an audience of thoughtful pre-teen and young teenage readers, but will not appeal to many in this age group. I also agree this has been published internationally and is receiving lots of publicity only because the author is already well-known and critically acclaimed – but hopefully this will encourage more publishers to take a chance with subtle, complex, realistic books for young teenage readers who find the sex and violence in some YA books a bit too much for their tastes.